Imprint # 310

Distributor: Via Vision Entertainment (Imprint)

Release Date: April 24, 2024

Region: Region Free

Length: 01:49:06

Video: 1080P (MPEG-4, AVC)

Main Audio:

5.1 English HD-DTS Surround Audio

2.0 English Mono Linear PCM Audio

Subtitles: English HOH

Ratio: 1.85:1

Notes: This title was released on Blu-ray by Twilight Time in 2012 and by Sony Pictures in 2021.

“I did Pal Joey with Frank over at Columbia. He was an unbelievable professional. He’s an amazing, great talent, with great sensitivity. I would say that he has greater knowledge of an orchestration than anybody. He knows more about a song than anyone. When we’d run through an orchestration, we’d watch him. If those shoulders went up in the air a little bit, something was wrong. He’s practically infallible with a song. His phrasing is magnificent. In that period when I was making musicals, it was the time of the musical giants — Judy Garland, Gene Kelly, Frank Sinatra, Fred Astaire. That’s what made those pictures great, along with the songwriters — Rodgers and Hart, Oscar Hammerstein, Irving Berlin, George and Ira Gershwin, Jerome Kern, Cole Porter. They made a difference. We made musicals because we had music.” —George Sidney (George Sidney: Son of an Entertainment Executive, Just Making Movies, 2005)

Pal Joey (1957) is an adaptation of a Broadway musical that opened at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre on December 25, 1940. This production ran for 374 performances with George Abbott directing Gene Kelly in the title role, Vivienne Segal as Vera, and June Havoc as Gladys. Van Johnson and Stanley Donen were also in the cast. The book was written by John O’Hara from his own stories that had appeared in The New Yorker. (The original stories were presented in the form of letters. They were signed, “Your Pal, Joey.”) The music was written by Richard Rodgers, and the lyrics were penned by Lorenz Hart. Unfortunately, the production actually led (indirectly) to a decline in Hart’s health.

“Hart, a heavy drinker, was ejected on the opening night for singing along with the performers. He disappeared into the night without a coat, and his health never recovered. His final words were ‘What have I lived for?’ but his legacy continues to this day.” —Spencer Leigh (Frank Sinatra: An Extraordinary Life, 2015)

The play ended up being popular but controversial. Anti-heroes and flawed characters hadn’t yet become a common ingredient in fiction, and critics seemed to believe that the charming but self-serving nightclub singer named Joey Evans at the heart of the story was too problematic to inspire audience interest. After all, how could anyone root for such a man? (Time has proven that such notions are ridiculous, but many critics still have similar archaic beliefs.) A review in the New York Times queried, “Can you draw sweet water from a foul well?”

Harry Cohen (the co-founder, president, and production director of Columbia Pictures) felt that “sweet water” could indeed be drawn from such a well if the proper cast for a screen version of the musical could be assembled. He purchased the screen rights and thought that he had an easy “hit” on his hands. His first attempt at bringing Pal Joey to cinema screens began in 1944 (more than a decade before it went into production). He had hoped to cast Gene Kelly in the role he originated on the stage with Rita Hayworth in the role of his younger love interest. Unfortunately, Kelly was under contract to MGM, and Cohn was unable to make an acceptable deal with them for the actor’s services. James Cagney and Cary Grant were both considered at one point, but Cohn soon became frustrated and temporarily shelved the project. Casting wasn’t even the biggest challenge that the production faced.

“‘Goddam movie,’ cursed Cohn. ‘Should never have bought the thing. It’s unfilmable!’

‘It was your decision Harry,’ said his long-time friend screenwriter Sidney Buchman. ‘I know it was,’ yelled Cohn. ‘Don’t remind me.’ For once he had no one to blame but himself.

In Hollywood, Cohn’s purchase of the screen rights of Pal Joey quickly became known as ‘Cohn’s Folly.’ Those close to the studio boss would occasionally taunt him with the words, ‘When are you going to film Pal Joey Harry?’ Cohn would glare, utter an expletive, and then go on to discuss his next production.

The reason for all the problems lay in the musical’s morality or rather the lack of it. Pal Joey was [about] a heel, an unscrupulous night-club entertainer who ditches the girl who adores him so that he can take up with a wealthy married woman who, in return for sexual favors, promises to set him up in his own night-club Chez Joey. Things go wrong. Ambition and greed get the better of him. In the end he is left as he was at the beginning, looking for the break that will never come and having ruined the lives of those around him….

…Cohn’s problem was that in the mid-forties the production code was stiff to the point of rigidity. Censorship was so tight there was no way that Joey’s activities could be convincingly portrayed on screen. Cohn, who had planned the film as a successor to his hugely popular Cover Girl (which had also teamed Kelly and Hayworth) had no option but to put the property on ice. He concentrated instead on other musicals, The Jolson Story and Jolson Sings Again. Their success at the box-office at least went some way to compensating for what he believed was the most serious mistake of his career.

Director Billy Wilder was one of the first to convince him that it might just be possible to get Pal Joey off the ground. He told Cohn that he saw the film as a kind of musical variation of his Hollywood story Sunset Boulevard in which a much younger man had also been kept by an older woman. He wouldn’t mind having a crack at the story. Was Cohn interested? Cohn was to the interested in anything that would get his long dormant musical on to the screen. He invited Wilder to dine with him at Columbia. Wilder put forward the suggestion that Joey be recast as drummer and that Marlon Brando should play the lead. Mae West, he said, would be ideal for the older woman.

It didn’t sound much like Pal Joey to Cohn, but he agreed to give it a go. Wilder moved into the Columbia offices with his typewriter. He stayed for ten days and then left. He was unable to lick the story and rework it into his own concept. It was the only time in his career that he had worked at Columbia. He never returned. Two weeks after his departure he received what he thought was a note from Harry Cohn, thanking him for his efforts. There was no thank-you note in the envelope. Just a bill for two lunches. Price: $5!

After Wilder there were others who ran ideas past Cohn. A Columbia executive suggested doing Pal Joey as an all-black musical. Carmen Jones had been a smash. It might be worth a try. The idea was dismissed. Then someone said how about Kirk Douglas. He had made a successful career out of playing heels. Cohn recalled films like Champion, Ace in the Hole and The Bad and the Beautiful. He liked the idea. ‘Great,’ he said. ‘Kirk’s a fine actor. Let’s talk!’

‘He can’t sing Harry,’ reminded an aide.

‘Forget it!’ snapped Cohn.

Marlene Dietrich’s name also came up. She was 56. She would be ideal as the woman who bankrolls Joey. Cohn was tempted. Dietrich wasn’t exactly box-office but if the actor playing opposite her was a big enough star the combination might be intriguing. Tentative enquiries were made. Dietrich was not averse to the idea. It was she who first brought Sinatra’s name into the casting game. ‘I’ll do it,’ she said. ‘But on one condition. I want Sinatra. If he plays Joey, I’ll sign right away.’

‘He doesn’t talk to me since From Here to Eternity,’ said Cohn glumly. ‘He won’t do it.’

‘No deal,’ said Dietrich.

Cohn tried a last gambit.

‘How about a young actor who’s just coming up on the Columbia lot?’

‘Who’s that?’

‘Jack Lemmon.’

‘He’s a nobody.’ End of discussion.

In the end it was director George Sidney who decided to pursue things with Sinatra. He had known Frank since they had filmed Anchors Aweigh together at Metro. He had since moved over to Columbia to try and bolster the studio’s musical image with a series of independent productions. Pal Joey, it was hoped, would be one of them. Over a drink one night he brought Sinatra’s name up once again. ‘Harry, you know as well as I do that there’s only one guy who can play Joey and that’s Frank. He was born to play Joey. Why don’t we give it a try?’

‘Okay, ask him,’ said Cohn wearily.

Sidney put the idea to Sinatra the very next day. Sinatra said ‘yes’ before he had finished the question. He even said he’d buy into the project with his own independent company, Essex Productions.

Next came the casting, something that Cohn was adamant about. He was insistent that Rita Hayworth get top billing. He also demanded that Kim Novak be given ‘the other lead role.’ How did Sinatra feel about that? He was now one of the world’s most popular movie-stars. His name guaranteed success. He had every right to kick up a fuss. ‘Are you kidding?’ he said when Sidney brought up the subject. ‘Rita is Columbia Pictures. She has been ever since she stepped foot on the lot. Besides, who wouldn’t agree to being in a sandwich between those two chicks,’ he added with a twinkle in his eye.” —Roy Pickard (Frank Sinatra at the Movies, 1994)

The primary reason that Sinatra was so agreeable is that he wanted the role every bit as much (and perhaps more) than Columbia wanted him to accept it. Of course, it seems likely that Roy Pickard’s account of these events are somewhat simplified. Michael Freedland suggests in “All the Way: A Biography of Frank Sinatra” that George Sidney’s wife, Lillian Burns, also played a role in Frank Sinatra’s casting. One might even say that Freedland’s account contradicts the Pickard biography, but seeing as how Burns and Sidney were a married couple at the time, it is very likely that both versions have some validity.

“Lillian Burns, Cohn’s aide-de-camp, was another who rejected the idea of Kirk Douglas. Ms. Burns, whose previous connections with Sinatra had been limited to the fact that she had given Ava [Gardner] elocution lessons, told me: ‘I always thought that Frank was born to play Joey.’ So her solution was to invite Cohn and Sinatra to her home to dinner. Abe Lastfogel, the boss of the William Morris agency, was invited, too. Lastfogel returned the next day to pick up the Joey treatment.

As Lillian Burns remembers:

‘A buzz came several days later that Mr. Lastfogel was on the phone. Remember that Harry Cohn had the big desk. There were Oscars behind and the machine in front of him on which he could get anyone in the studio. He put the call on the speaker. We had a bet — a box of cigars against a bottle of perfume — that Frank wouldn’t do it. Abe said, ‘‘Frank loves it.’’ I could see Harry’s face — it meant he would have to give me a bottle of perfume.’

Jonie Taps claims that he was the one who finalized the deal. ‘It took two years for it to be done,’ he told me: ‘I was in Las Vegas and met some of the men from the Morris agency. I asked them for Sinatra. They said yes, and I then made sure that he got the score of the picture. Harry Cohn wasn’t happy. ‘‘Schmuck!’’ he told me, ‘‘that’s ‘ as good as a contract.’’ I said, ‘‘Yes, Sinatra’s word is as good as anyone else’s contract.’’ Which, of course, is not what everyone else says.’” —Michael Freedland (All the Way: A Biography of Frank Sinatra, 1997 / 1998)

Abe Lastfogel was able to negotiate a very good deal for Sinatra. The crooner would receive $125,000 in addition to 25% of the profits for portraying a character that he already believed that he was born to inhabit. The money would purchase him a new home in Palm Springs (where he would later build a restaurant called “Pal Joey’s”).

“Sinatra reveled in recreating Joey for the screen. He brought precisely the right amount of brashness and arrogance to the role and at the same time, through his own personality, softened Joey just enough to make him acceptable to movie audiences. He was still unscrupulous, still a climber, still a heel — but a likeable heel.

Sinatra reveled too in the songs. Cohn had been ruthless with the original score. He had cut eight of the twelve original ‘Pal Joey’ numbers and substituted in their stead such vintage Rodgers and Hart hits as ‘I Didn’t Know What Time It Was,’ ‘There’s a Small Hotel,’ ‘My Funny Valentine,’ and ‘What Do I Care for A Dame?’ It might not have been the original [play] but it was a feast for Sinatra.

The stand-out number was suggested by George Sidney. It had featured in the 1937 Broadway hit ‘Babes in Arms’ when it had been sung by Mitzi Green. The song was ‘The Lady is a Tramp.’ ‘That’s a woman’s song,’ scoffed Cohn. ‘Sinatra will never sing that.’

‘He’ll go for it,’ said Sidney, confidently. ‘I’ll talk with him.’ But when he did bring it up during the pre-production planning of the movie the response was not what he had expected. Sinatra’s reaction was cool. He showed no enthusiasm whatsoever. Sidney was forced to assume that on this occasion Cohn was right. He put the song aside as a non-starter.

Then came the call. Sinatra had just finished The Joker Is Wild [1957] and was in Vegas at the Sands. Sidney said:

‘I got this telephone call. It was Frank. He said, ‘‘Why don’t you come up George. I’ve got a little something for you.’’ Sinatra was doing two shows a night then (can you imagine what that would cost today?) and in those days he would sing ten numbers straight, one after the ether and practically never stop, even for applause. I’d dropped in to see him in his dressing room before the show and asked him what it was [that] he wanted but he said, ‘‘Later George, go out front and have some dinner and catch the show.’’

Well, he was well into his set numbers when right out of the blue came ‘Lady is a Tramp.’ I wasn’t expecting it, nor was anyone else for that matter, and he just tore the place apart. I’d never heard such a response to a song. Later, he came out and with a broad grin said, ‘‘How do you like my new song?’’ That was Frank!’” —Roy Pickard (Frank Sinatra at the Movies, 1994)

Kim Novak was less enthusiastic about her role in the film. She didn’t particularly like the character that she was being asked to inhabit, and she was always very vocal about this fact. “I didn’t like playing her. She’s the kind of person who’s so ambitious it makes you sick,” Novak insisted. “I can’t even stand the name.” Of course, it didn’t help that the actress was exhausted from the physical and mental demands of portraying Jeanne Eagels just prior to being pushed into this project.

“Just when Kim was ready to ask Harry for a furlough, he decided to use her in a major musical film, Pal Joey. Director George Sidney, who had also guided Jeanne Eagels, campaigned for the casting. ‘She’s perfect for this part, Harry,’ the director explained. ‘In fact, I don’t know any other actress who could play the part half as well.’

So, it was done. Kim was told (not asked) to appear opposite Sinatra and Rita Hayworth in the Rodgers and Hart musical. … It put terrible pressure on Kim — who could neither dance nor sing. She appealed to Max Arnow: ‘This won’t work. I can’t get ready in time.’

The studio responded by arranging dance and vocal lessons in a special studio on the lot. For weeks, from eight a.m. until after nine at night, Kim worked on routines for the film. And Mac watched helplessly as she visibly melted under the pressure. One afternoon she practiced a dance routine so endlessly that her feet began bleeding and she had to be rushed to the infirmary. There, doctors had to cut off her shoes. Frank Sinatra learned of her dilemma and comforted her with a series of calls. ‘It won’t be that hard. Trust me,’ he said.

During the first week of filming, however, Kim collapsed in her dressing room. She told reporters, ‘I’ve been having agonizing headaches, and I can’t sleep. For the first time in my life, I’m having trouble with my health. And when the doctors ordered me into a hospital this time I gave them no argument.’ After several days in a hospital, she retired to a rented home in Malibu to recuperate. Her scenes were postponed as filming continued choppily on Pal Joey.

When he learned of the collapse, Cohn was visibly touched for the first time. He bragged to Louella Parsons: ‘Do you know what that girl was doing? She was dancing all day … until she couldn’t stand up any longer.’ Kim resumed work a month later.

Most of the time, Kim and Rita appeared in different scenes shot on separate soundstages. But in a crucial dream sequence, the stars appeared together in a choreographed routine, a mild ballet set to Richard Rodgers’s music. Everybody at Columbia, even Harry Cohn, expected fireworks when the thirty-eight-year-old film queen and her upstart successor met for the first time. Reporters skulked about the set, expecting (and hoping for) the worst, but it all went off without a hitch.

Rita wore a gorgeous silk pantsuit and never looked lovelier. Kim, on the other hand, appeared wan and ill at ease. She seemed somewhat lost in the huge production number. During dress rehearsals, the set remained open to all comers — including a growing line of reporters. But the morning the cameras rolled, the doors were locked and guarded by a flank of security police — making the action inside all the more irresistible.

Harry slipped in just as the dance wound up and watched Kim and Rita from the shadows. As they danced through a curling bank of artificial fog, Cohn whispered to Max, ‘There they are — my first star and my last.’

‘What do you mean, ‘‘last star,’’ Harry?’ Max asked. Cohn turned his face away. ‘I just have a feeling that Kim will be my last star, Max.’

During a break in the shooting, Rita was interviewed by columnist Sidney Skolsky. He pointed across the lot to Kim Novak and asked, ‘Are you envious? Do you wish you were back in the early days?’

‘Not for a million dollars, Sidney. I don’t envy her one bit.’” —Peter Harry Brown (Kim Novak: Reluctant Goddess, 1986)

It might be difficult for some readers to understand why people would automatically assume that Hayworth and Novak would have interpersonal issues. Barbara Leaming explains this quite well in “If This Was Happiness: A Biography of Rita Hayworth,” but her account of Hayworth’s experience during the production only reinforces Peter Harry Brown account of events (albeit from Hayworth’s perspective).

“The creation of Kim Novak as Columbia’s next ‘big star’ was widely thought to be Harry Cohn’s revenge on Rita, so that putting the two actresses together made the press and public expect fireworks. Still, according to George Sidney, on the set ‘there was no friction between Rita and Kim.’ Although Rita did lament that she was actually younger than Frank Sinatra, she was really just anxious to fulfill her final obligations to the studio as quickly and smoothly as possible. ‘She comes in, you tell her what to do, she does it,’ as George Sidney would characterize her consummate professionalism during Pal Joey. ‘We were shooting on location in San Francisco, and it was bloody cold. I had on three overcoats. Rita had a little chiffon dress on. The wind was howling. I said, ‘‘Come on, we’ll shoot in the studio.’’ She said, ‘‘No, please, stay with it.’’ I said, ‘‘Come here.’’ I grabbed her and she was absolutely purple. The pigment had changed, it was that cold.’

The bitter cold wasn’t the only trial Rita had to contend with in San Francisco. Again (although this time she had worked hard to get into shape for the part) there were hurtful remarks about her loss of youth. Rita’s stand-in, Grace Godino, recalled one such painful incident: ‘It was at night. We were shooting outside, and the crowds had gathered around for autographs. Frank had gone somewhere else. But Rita and Kim were there, and a crowd of people came up to get Kim’s autograph. Then as they started toward Rita, somebody said in one of those inimitable rude fan voices, ‘‘Oh, she looks so old!’’ Rita just blanked out. She acted like it didn’t bother her, but it must have hurt.’

There were also moments when Rita seemed quite content to pass the torch (and all that went with it) to the younger actress. Thus, Grace Godino would recall the day back in Hollywood when ‘Kim Novak’s costume split at the dress rehearsal and there was big hullabaloo. Kim got hysterical and of course the wardrobe lady was in tears. Harry Cohn came on the set and the whole production stopped while they all went on about this. But Rita was at that period of life when it just wasn’t important to her. She walked over to her chair and sat there with that cute smile of hers. She didn’t have to say it but you could just sense she thought, ‘‘Let them have their fun. Here’s the new sexpot they’re going to have to worry about. I don’t have to worry about that anymore.’’’” —Barbara Leaming (If This Was Happiness: A Biography of Rita Hayworth, 1989)

While Hayworth and Novak behaved professionally towards one another, Novak did manage to clash with Barbara Nichols (who was cast as a stripper named Gladys). Nichols had appeared in the 1952 Broadway revival of ‘Pal Joey’ and appearantly had the same shade of blonde hair as Novak.

“Kim told Sidney to urge Barbara to change [her hair color] voluntarily, but when she refused, Kim appealed to a higher authority, and an order came down from Cohn. The two girls didn’t speak during filming.” —Peter Harry Brown (Kim Novak: Reluctant Goddess, 1986)

Other versions of the story don’t lay the blame on Novak but instead claim that George Sidney and Harry Cohn were more concerned with the similarities in their hair color than Novak. Either way, Nichols blamed Novak. This, however, was a minor hiccup in a mostly smooth production. What’s more, Novak’s hospitalization (which certainly wasn’t her fault) may have made for a “choppy” shoot, but the film managed to finish on time. In fact, George Sidney remembered finishing ahead of schedule despite Sinatra’s unusual scheduling preferences.

“Frank decided that it would be better to work in the afternoon rather than in the morning, so we started working at one o’clock. We worked from one till eight every day. We whizzed through that picture and finished a number of days under schedule. Frank would come in and he’d be wound up ready to go, and we’d knock off two or three days work at a time. It was great fun.” —George Sidney (George Sidney: Son of an Entertainment Executive, Just Making Movies, 2005)

It might also be worth mentioning (as a piece of interesting trivia) that the production marked the first time that the “Hollywood Helium Bath” was used. Pipes were placed under the tub, and helium was fed into the water to create an increase in the volume of the soap suds. This allowed the filmmakers to photograph both actresses in the bath without sacrificing their modesty.

It seems that Novak’s vocal training for the role was a waste of her much-needed energy, because both of the female leads were dubbed for their musical numbers (just as Sinatra’s piano playing was actually provided by Bill Miller).

“Rita’s songs were dubbed by Jo Ann Greer and Kim’s by Trudi Erwin. Again, as in 3 Against the House, after extensive singing training, Kim’s voice would be heard only briefly in two numbers where she talk-sang a line or two. (‘Don’t you know your Mama’s got a heart of gold?’ in the ‘I’m A Red Hot Mama’ number, and the opening strains of ‘My Funny Valentine.’) … In the shaping of the legit hit for the screen, a number of switches were pulled. The role that Kim played was built up from the minor one it had been on the stage to star status. Despite this, however, it remained weak and suffered in comparison with the Hayworth and Sinatra parts.” —Larry Kleno (Kim Novak on Camera, 1980)

The enhancements made to Novak’s character and the reworking of the musical score weren’t the only alterations made to the original play. The production code would force Dorothy Kingsley (the screenwriter) to make other adjustments when adapting the film for the screen. Some of these changes were minor. For example, a number of dialogue adjustments were made to soften moments that weren’t considered appropriate. In addition to these changes, Rita Hayworth’s character was a married woman in the original stage version, and she was made a widow in the screenplay.

Of course, some of the changes were made for aesthetic purposes, and the most notable of these might be the change in setting from Chicago to the more picturesque San Francisco. Of course, there were practical reasons for this change as well. It was believed that San Francisco would result in fewer weather-related problems.

“Location filming resulted in shots of Golden Gate’s Sausalito Yacht Basin, Fisherman’s Wharf, Coit Tower, the St. Francis Yacht Basin, the Oakland-San Francisco ferry, the Spreckels mansion, and Market Street. Ironically, the company was rained out of its fair-weather location and had to return to the studio a week earlier than planned.” —Larry Kleno (Kim Novak on Camera, 1980)

Finally, the ending was changed from the original play. As Roy Pickard writes in “Frank Sinatra at the Movies,” Kingsley opted for “a happy ending with Sinatra and Novak heading towards the Frisco Bridge and a rainbowed future.” George Sidney wasn’t entirely satisfied with the film’s new ending. “I don’t believe there were too many in the audience who swallowed all that,” the director lamented. “I think they thought as I did. That the minute the bum got across the bridge he’d be off.” He accepted the ending because he understood that it might help to placate the censors.

“[Unfortunately], even with all the changes and the toning down there were still problems. George Sidney explained:

‘I’d never had any problems with censorship in my life. But all of a sudden, we heard there were problems with the film in New York. So I went to New York to find out what the trouble was all about.

There was a thing they ran in those days called ‘‘The Legion of Decency’’ and a whole bunch of women had been complaining. Anyway, we ran the film and when it was over the women came over to me and said, ‘‘It’s the story of a pimp.’’

I said, ‘‘Really? Please give me a dictionary and tell me what a pimp is?’’ Well, a pimp was far from what Pal Joey was so that knocked that one down.

Then they said, ‘‘Sinatra was a married man.’’

(He was still married to Ava then) and I said, ‘‘Where does want to Frank Sinatra appear up on the screen?’’ I said it’s a character. ‘‘Do you get into my personal life? What about the cameraman? He’s been married six times you know. All this is ridiculous.’’

Well, in the end they had nothing to say about it. There were no cuts, nothing. I couldn’t believe the people I was dealing with. They were so far round Robin Hood’s barn … as for Joey being a pimp. A pimp is a fellow who’ll go up and down Sunset Boulevard. We have charming scenery here these days. And you know, he’ll make a deal. That’s pimping. It’s a very old business. I hear profitable.’

When he viewed the finished film at Columbia Studios on Gower Street, Harry Cohn knew he was a lucky son-of-a-bitch. He had the last laugh on Hollywood after all. He usually did, he was a canny devil and had an instinctive feel for what the public wanted but there had been more than one occasion since he had purchased the rights to Pal Joey when he felt that, just for a change, Hollywood might have the last laugh on him. It didn’t happen. As Pal Joey unspooled on screen before him, he knew he had a great popular musical on his hands. Sinatra was sensational; ‘Lady is a Tramp’ was a knockout; Rita looked great; the orchestrations were superb. The whole film entertained. There was a song every ten minutes, sometimes there were two in that time. What gratified him most was that the film moved.

When someone reminded him that they were also releasing another prestigious film that fall — David Lean’s classic war film The Bridge on the River Kwai — he shook his head. ‘Great film, could win us a lot of Oscars. But it’s 163 minutes. That’s too long. Two hours is the maximum for a Columbia movie. Pal Joey is Columbia’s film of the year.’” —Roy Pickard (Frank Sinatra at the Movies, 1994)

Cohn was wrong. The Bridge on the River Kwai was a bigger and more successful film in every respect. It earned a $27,200,000 at the box-office domestically (with a worldwide total of ($27,200,463). It was easily the most successful film released by Columbia that year. Meanwhile, Pal Joey was more of a succès d’estime by most accounts.

Different scholars have different perceptions as to the level of success that the film actually enjoyed. Larry Kleno claims that “stockholders were riding high” because the film grossed “$4.7 million in domestic rentals alone” on Columbia’s 2.7 million investment, while Peter Harry Brown maintains that “it was a disappointment and didn’t earn back its cost until two years later… when it was sold to television.” Spencer Leigh, on the other hand, splits the difference and reports that “the film did moderately well at the box office and made its profit from TV sales.” Variety did list the film as one of the ten highest-earning films of 1957, so it is fair to say that it was far from a failure.

It was certainly given its fair share of publicity.

“[Cohn] told Sidney that he wanted a big preview for the picture, one of the biggest Columbia had ever staged. ‘OK Harry,’ said Sidney. ‘We’ll go to New York and show ‘em what we’ve got. We’ll book a theatre for the night and invite everybody, all the people from Broadway.’ Sidney remembered later:

‘It really was one helluva night. I spent the entire evening in the meat box. That’s where you can control the sound and this, that, and the other. I knew that unless it was done properly, we were going to be killed. The Mermans, the Logans, everybody was there. We really had to do it in style. When we got to ‘‘Lady is a Tramp’’ I just opened the box wide. I blew one of the speakers but there were six others, so it was all right. Well, the audience they screamed, they cheered, they did everything … it was so wonderful. Harry was over the moon.’” —Roy Pickard (Frank Sinatra at the Movies, 1994)

Variety’s review encapsulates the overall critical reception rather well.

“Pal Joey is a strong, funny entertainment. Dorothy Kingsley’s screenplay, from John O’Hara’s book, is skillful rewriting, with colorful characters and solid story built around the Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart songs. … Kingsley pulled some switches in shaping the [original play] for the screen…

…Frank Sinatra is potent. He’s almost ideal as the irreverent, free-wheeling, glib Joey, delivering the rapid-fire cracks in a fashion that wrings out the full deeper-than-pale blue comedy potentials. Point might be made, though, that it’s hard to figure why all the mice fall for this rat. Kim Novak is one of the mice (term refers to the nitery gals) and rates high as ever in the looks department, but her turn is pallid in contrast with the forceful job done by Sinatra.

Hayworth, no longer the ingénue, moves with authority as Joey’s sponsor and does the ‘Zip’ song visuals in such fiery, amusing style as to rate an encore. Standout of the score is ‘Lady Is a Tramp.’ It’s a wham arrangement and Sinatra gives it powerhouse delivery.” —Staff Writer (Variety, December 31, 1936)

One will notice that praise is heaped upon Sinatra’s performance even as they condescendingly criticize Novak’s acting ability. This would become a pattern. As the New York Times suggests in their review: “This is largely Mr. Sinatra’s show. … He projects a distinctly bouncy likeable personality into an unusual role, and his rendition of the top tunes — notably ‘The Lady Is a Tramp’ and ‘Small Hotel,’ gives added luster to these indestructible standards.”

Meanwhile, Look magazine enthused that “Frank Sinatra plays Joey with all the brass the role demands. He has a gleam in his eye and a chip on his shoulder, as he portrays this unsavory character who could be so charming — against everybody’s better judgment. He tosses off both dames and songs with equal artistry.”

Dilys Powell’s review in London’s Sunday Times agreed, and she even described the audience’s reaction to Sinatra: “When at the showing the other afternoon we came to the point at which, for the benefit of the society woman visiting the third-rate night-club, he insolently sings ‘that’s why the lady is a tramp’ there was a burst of applause from the audience and though these critical hands are not exactly horny with clapping I almost joined in.”

The review that appeared in The Hollywood Reporter was a virtual love letter to the crooner: “Sinatra does not cheat at all in his characterization. His Joey is as glittering and vulgar as a three-carat little finger ring and still — and here is O’Hara’s contribution — you are utterly fascinated with his nasty little heel. You pull for his come-uppance but still, when he gets that kick in the teeth, you hope it does not disarrange them too much.”

Unfortunately, many reviews would single out Kim Novak as the film’s weak link. In fact, a few critics were nearly hostile. For example, a review published in Photoplay magazine complained that the actress “has no personality beyond a publicity handout, and has outstripped her meagre talent,” and William K. Zinsser wrote in a review for the New York Herald-Tribune that Novak had “reduced her acting technique to the process of rolling her huge eyes back and forth like pinballs, in the manner of silent film stars, and since she says almost nothing she might as well be in a silent film.’

However, Larry Kleno has made the observation that “the early part of the picture gave Kim very little dialogue” and suggests that “there wasn’t much she could do except use her eyes.” He also points out that “Hayworth and Sinatra were a powerful pair to be pitted against. Theirs were the strongest parts, and their experience vastly overshadowed hers.” While it is difficult to argue against the fact that her performance pales in comparison to her two co-stars, it is important to remember that much of this had more to do with the fact that her role was underdeveloped. The hostility towards her was cruel, unfair, and unnecessary.

“It was not surprising, after this film, that Kim thought her career might be at an end. As she put it:

‘I was good in my first picture and got wonderful reviews. I was afraid I might not be able to live up to them. I felt it could never happen again. Today I’m worried because I didn’t enjoy it on the way up, and now maybe I’m on the way down.’

The whole incident suggested that Kim could not be really convincing in anything she herself didn’t believe. She had not been overjoyed with either the character or the role, and her hunch about them had been right. Seen today, her performance in Pal Joey is not one of her best. It almost appears to be two separate performances. During the first half of the film, when there isn’t much to say or do, she functions as if she were in a trance; it isn’t until the second half that she comes into her own.

It is interesting to note that, in a drunk scene here, she fell flat, while, in a similar one in Jeanne Eagels, she was totally right. Same director. Same star. It looked as if she were trying to duplicate the scene in Pal Joey — and that may be where the problem started.” —Larry Kleno (Kim Novak on Camera, 1980)

All of this was merely a hurtful hiccup to an otherwise successful release. Pal Joey was nominated in four categories at the 30th Annual Academy Awards — including Best Art Direction (Walter Holscher, William Kiernan, & Louis Diage), Best Film Editing (Viola Lawrence and Jerome Thoms), Best Costume Design (Jean Louis), and Best Sound Recording (John P. Livadary) — even if it didn’t end up winning in any of these categories. However, Frank Sinatra did win a Golden Globe for his performance in the film, and the HFPA also nominated the film in the Best Film – Comedy or Musical category. If this can’t objectively be called “success,” then they must have altered the definition when nobody was looking.

“It was one of Columbia’s biggest ever musical successes. It was also one of the last enjoyed by Harry Cohn. In February 1958, just a few months after the premiere of Pal Joey, the film that had caused him trouble for almost fifteen years, he succumbed to cancer. … George Sidney still rates Pal Joey as his best screen musical — superior to anything he accomplished at MGM.” —Roy Pickard (Frank Sinatra at the Movies, 1994)

In the end, one’s enjoyment of the film will depend upon their personal tastes. Those who enjoy screen musicals and Frank Sinatra’s crooning will probably love it.

The Presentation:

5 of 5 Stars

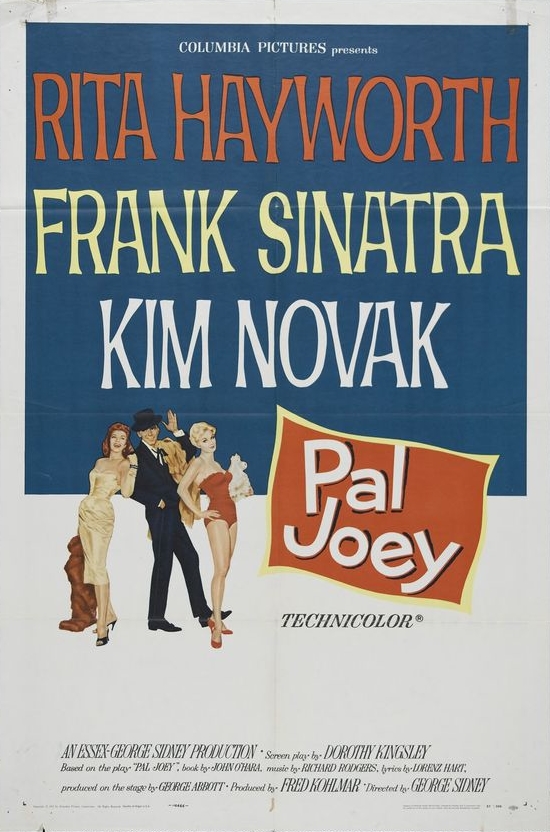

Via Vision Entertainment protects the disc in a clear Blu-ray case with a dual sided insert sleeve that features artwork that is essentially a slightly altered version of the film’s original theatrical one sheet design. They have cropped out the credits at the bottom of the image and the negative space above the three actor’s names at the top of the image, but the design is otherwise left intact. (Spencer Leigh suggests in “Frank Sinatra: An Extraordinary Life” that Sinatra even came up with the concept for this design. Much like the billing, the actor appeared with Rita Hayworth and Kim Novak on each side of him. “People will think, ‘Gee, I’d like to be that fella. What a sandwich,’” he joked.) The interior includes a production still from one of the film’s scenes.

All of the movies included in the “Film Focus: Kim Novak” collection fit into a very sturdy box that is incredibly attractive. Of course, those who wish to own the boxed set will need to act fast because this is a Limited Edition (only 1500 copies exist).

It is worth noting that the rating label is on the plastic wrapping and not on the actual box (nor is it on any of the individual insert sleeves for the films in this collection), so it does not mar the packaging in any way.

The disc’s static menu features attractive film related artwork and is intuitive to navigate.

Picture Quality:

4 of 5 Stars

The back of Via Vision’s packaging promises a Blu-ray presentation of a 4K scan of the original negative, and the transfer is really quite solid (even if it doesn’t quite rise to the level that one expects from high-definition transfers that have been taken from a 4K master. There is a softness to Harold Lipstein’s cinematography that is in keeping with 1950s cinema, but the colors are as bright and vivid as one expects from musicals of the period as well (and these seem to be accurately represented throughout the duration). There is a slight decrease in perceived detail during certain sequences which use optical effects, but fine detail typically impresses throughout most of the film. Depth and clarity are also solid and seem accurately represented for the most part. Fans should be fairly pleased.

Sound Quality:

4 of 5 Stars

Sound is especially important when the film is a musical, so fans will be pleased to learn that Via Vision has provided a pair of very nice lossless options. The original monophonic soundtrack is presented as a 2.0 LPCM audio track, and a 5.1 surround remix is presented as a HD-DTS Audio track. Both options are well rendered with the 2.0 offering purists a clean and clear rendering of the original mix while the 5.1 option offers a slightly more dynamic presentation. Some of the music can sound slightly boxed in (which is a shame), but this seems to be inherited from the production methodology of the late 1950s. It should be said that the music sounds quite impressive for the most part, and this disc should be a real treat for Sinatra fans.

Certain audiophiles may also wish that the 5.1 track was more immersive, but one can only do so much with tracks that weren’t produced to become surround tracks in the first place. It is important to have reasonable expectations. It is a decent re-mix that doesn’t try to completely reinvent the wheel.

Special Features:

3.5 of 5 Stars

Select Scene Audio Commentary by Kim Novak and Stephen Rebello — (11:41)

For the most part, this “select scene” commentary feels more like a conversation or an interview than a typical commentary track. There is very little here that could be described as “scene specific,” but it is actually nice to hear Novak discuss the film. Her comments about the film are always diplomatic, and she discusses her two co-stars with fondness. It is nice to hear a few of her thoughts about the film (although she hints that her character in the film didn’t really give her a lot to do). We learn that she wishes that they had used her less polished recording of “My Funny Valentine,” but that Harry Cohn wanted a more polish rendering of the song (as was the custom at the time). There’s plenty here to make it worth a listen.

Backstage and at Home with Kim Novak — (09:27)

This featurette from 2010 blends footage of Pal Joey with footage of Novak at home (she has a beautiful property in Oregon) as she discusses a handful of topics with Stephen Rebello — including her preference for Jean Louis as a costume designer over other designers such as Edith Head, her retreat from Hollywood and acting, her painting, and the history of her home. This is a worthwhile addition to the disc that Novak fans will be happy to have.

Theatrical Trailer — (04:58)

Frank Sinatra hosts this unusual trailer (which could use a restoration). It’s nice to have it included on the disc.

Final Words:

Pal Joey is a charming screen musical even if it does fall short of perfection. It earns an easy recommendation for Frank Sinatra fans, and this Imprint Edition is probably the best way for them to experience the film in their home environment.

Note: While we were provided with a screener for review purposes, this had no bearing on our review process. We do not feel under any obligation to hand out positive reviews.

2 thoughts on “Blu-ray Review: Pal Joey”